Definition of Network and notes of terminology

The scope of palliative medicine has shifted during the past two decades, gaining a broader meaning and expanding the theory of hospice care to a more comprehensive “supportive care” paradigm. The patient type, also, shifted from the terminally ill cancer patient alone to every person affected by incurable and rapidly progressive pathologies (terminal COPD, end-stage heart failure, severe liver failure, etc) leading to basically the same care needs during the last weeks or days of life on one hand, but requiring specific and different approaches in the early stages on the other. The WHO definition of Palliative Care includes terms such as “prevention”, “early identification” and “impeccable assessment” strongly underlining that palliation is not relegated to the care of the dying only, but has a much wider application field, thus requiring a network of several and specific infrastructures, as well as human and instrumental resources. As far as Palliative Care for children is concerned, the WHO definition clearly states that “it begins when illness is diagnosed”. While the terms “teamwork” and “multidisciplinarity” often suggest the idea of “networking”, for the aims of this chapter the term Network will address to the set-up and interconnection among different care settings. Recently, a law issued by the Italian government [Law 38/2010 (1)] defines and establishes the national network for palliative care as a series of care facilities, professionals and procedures devoted to guarantee the best treatment during all the phases of the illness nationwide. The same law also defines a separate network for non-malignant chronic pain, which shape seems to follow to the hub & spoke model, where the hub frequently is the University/Hospital based Pain Clinic. In the case of palliative care, it is difficult to imagine pre-determined hubs, since the main place of care is time to time influenced by the patient’s wish and considering his/her family and social environment, and the economical situation, factors generally tending to worsen as the illness goes ahead. Even in the last days of life, when it is generally assumed that there is no place like home, statistics about where people choose to die are supported by little hard evidence, despite two paradoxes are generally observed: 1) most dying people would prefer to remain at home but most of them die in Institutions, and 2) most of the final year is spent at home but most people are admitted to hospital to die (2).

Current barriers to the development of palliative care

Many authors worldwide depict the status and advancement of palliative care in their own countries and seem to agree about the fact that its distribution is “patchy” and often geopolitical situations dictate the quality of care even in the same area. A report released by the Quality End-of-Life Care Coalition of Canada, stated that the majority of canadians want to die at home, but 60% die in Hospitals, due to the imbalance between the services offered in rural areas compared to the urban ones (3). In other countries fundings are mostly provided to cancer patients, so 500.000 people dying every year in the United Kingdom don’t receive adequate care and support because they don’t “fit a profile” (4). In Belgium, most patients have formal caregivers but the provision of specialist palliative care is less frequent, and the transition from cure to palliation often occurs late in the dying process and sometimes not at all (5). In 2007, an italian report indicated that palliative care services were not equally available across the country, being the access strongly associated with socio-demographic characteristics of the patients and their caregivers (the report considered cancer patients only) (6), despite a law issued eight years earlier (Law 39/1999) granted the Citizens’ right to access palliative care nationwide. The main barriers to the development of palliative care in Western, Central and Eastern Europe seem to be 1) the lack of financial and material resources, 2) problems related to the opioid availability, 3) lack of public awareness and government recognition of palliative care as a field of specialization, and 4) the lack of palliative care education and training programs (Central and Eastern Europe); despite a stronger availability of resources in Western Europe, ad uneven palliative care coverage and – particularly – lack of coordination amongst services has been described (7,8). Law 38/2010 claims to be very innovative at european level and establishes the transition from the hospice care paradigm to an interconnected network of health services and facilities, where the central hub is the person rather than a specific, “best”, place of care. This model represents a real challenge for the Italian regional governments, because for health managers it would be certainly easier to centralize patients and resources instead of having them distributed. Furthermore, the benefits of such law have been included in the Essential Levels of Care (LEA) “basket”, which constitute the italian Constitutional Right to Health, so that not granting LEAs represents an offence or crime against the Constitution.

The Network components

A recent report issued by the Italian Chamber of Deputies (9) about the impact of Law 38 one year after its promulgation states that the situation remains uneven nationwide, and that 15,5% of palliative care fulfills or is above the standards in a network perspective. Also, the same term seems to assume different meanings, so that many district declared they already had a “network”, eventually proven not to be adherent to Law 38. Ideally, the Palliative Care Network is a functional aggregation of health and social services, procedures and infrastructures often already existing in a specific area. These services include 1) Family Doctor/General Practitioner, 2) Integrated Home Care (IHC), 3) Specialistic Pain and Palliative Home Care, 4) Ambulatory Palliative Care, 5) Day Hospice/Day Hospital Care, 6) Hospital/Hospice Care.

While Family Medicine and Integrated Home Care are realities well known among population in different countries, other health services are much less known and poorly represented in the literature. A PubMed search with the string “Hospice” in the article title (only) returns more than 4.000 results, but less than 10 articles containing the exact string “Day Hospice” or “Ambulatory Palliative Care” can be found, including just two reviews. Despite it’s only a very rough estimate without statistical purposes, a Google Internet search returns more than 200.000 entries for “Day Hospice” (exact string) and more than 10.000 for “Ambulatory Palliative Care” (exact string). A certain amount of these documents belong to institutional / governmental web sites, including Hospitals and organization offering such services, this fact suggesting the idea that the general awareness is growing but the scientific evidence is still insubstantial, so that a cultural growth, and a thicker and more consistent consensus are needed. In 2009, a survey issued by the Italian Palliative Care Observatory (OICP, www.oicp.org) in association with the Mario Negri Pharmacological Reseach Institute, and involving 54 Palliative Care Centres (64% Northern Italy, 17% Central Italy, 19% Southern Italy), revealed the existence of 33 Ambulatory Palliative Care and Day Hospice services (10).

According to the various National/Regional/Federal/Local Health Systems existing in different countries, there is a ratio between public services and private services. As far as Italy is concerned, for example, Integrated Home Care is provided by public (64,6%) and private (35,4%) organizations. In order to be networked, both public and private services must meet common criteria (infrastructure, staff, procedures, workflows) dictated by the Health System and certified by proper accreditation agencies, and updated on a regular basis. Despite each single service (i.e., Hospice, IHC) is generally composed of a “network” of staff (doctors, nurses, psychologists, physical therapists, religious and social support, etc) and resources, the term here refers to the interconnection of the various “care settings” insisting on the same territory. Also important seems to be the inter-networking among different staffs (Palliative Care Centre and Health Districts, Pharmaceutical services, etc). As far as the Palliative Care Centres and the Pharmaceutical services are concerned, it must be said that it’s crucial to have a smooth and clear interaction, also using softwares to plan the weekly, monthly and yearly needs. In some cases, the Pharmacy “serves” different wards and hospitals (including mobile teams), providing patient-specific drug preparations (analgesic, anti-emetic, etc) (Table 1).

Table 1 – Increasing number of preparations (elastomeric pumps, electronic pumps refills, pediatric elastomeric pumps) provided by the Pharmaceutical Department of the “Maggiore Della Carità” Hospital in Novara, Italy, in favour of wards and Pain Clinic (from “Maggiore Informazione”, journal of the “Maggiore della Carità” University Hospital in Novara, 2008).

The Network workflows

In other fields of Medicine, such as Emergency Medicine, a good example of integration among services is represented by the pre-hospital and hospital Emergency Medical Systems (EMS), whose activation mostly relies on the public awareness of the existence of a unique emergency number to call (112 in most european Countries, 911 in the USA). It is based on the “Hub & Spoke” (H&S) model, where the spokes, or “entry points”, are peripheral facilities selecting and triaging the Patients in order to centralize them towards the main best healthcare infrastructure. Despite the hub / spoke flow can be bidirectional, generally a single Patient is admitted to the hub just once during the illness (for example, a small Hospital transfers a Patient to a bigger Hospital for specific procedures and eventually re-admits him/her when stabilized) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Hub & Spoke network vs other network design suitable for Palliative Care

On both graphs, the x axis is the life span, or the residual life span (in the case of terminal illness), the y axis the intensity of care. A) The H&S network model in the case of a young man having a car accident at the age of 20 (2nd spike), requiring EMS transportation and admission to Trauma Centre (Hub). B) The case of a person suffering for terminal illness, requiring constantly a high level of care. In this case, frequent access to the Emergency network and frequent admissions to Emergency Rooms stand for a poor quality Palliative Care program (eg. a non well-established network specific for Palliative support)

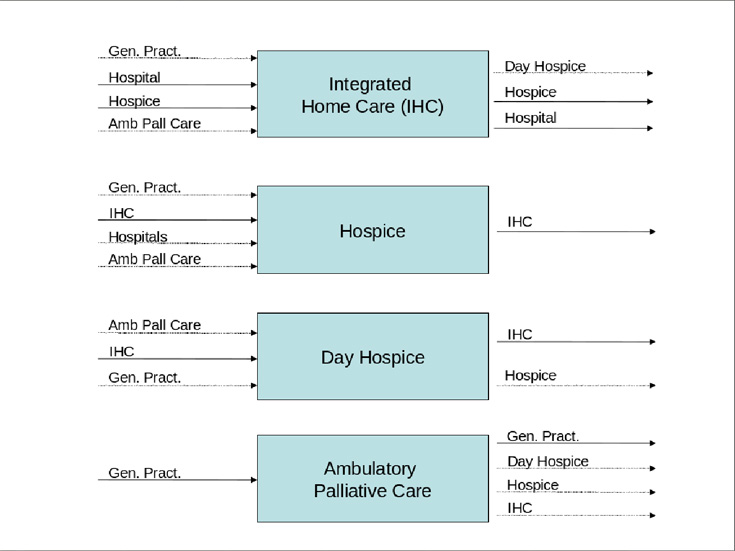

Differently from this model, the “entry points” in a Palliative Care Network may be many and not necessarily leading to the “centralization” of Patients in pre-determined structures. Nevertheless, the need for admission and take in charge may be dramatically urgent due to uncontrollable symptoms, disruption of the social and family environment and support, economical problems and so on. Integrated Home Care (IHC) services, Hospices, Day Hospices and Ambulatory Palliative Care facilities have entry points and discharge options (Figure 2), and the same Patient, differently from the H&S paradigm, could be readmitted several times to each facility, thus changing the care setting according to his/her needs.

Figure 2 – The main components/services of the Network as described in Law 38/2010. For each component the most common “entry points” (on the left) and the possible “discharge options” (on the right) are indicated.

For example, the admission to the IHC service is generally requested on behalf of Patients by General Practitioners and Hospital doctors, as well as by Hospice and Ambulatory doctors. If needed, the discharge options could include Hospice (re)admission and also the previous GP/Ambulatory care based setting if the Patient regains a certain degree of independence. Emergency Department admission and re-hospitalization are a generally distressing and exhausting possibility, representing an indicator of poor-quality in community based palliative care (11,12).

Requests for Hospice care may come from General Practitioners, Hospital doctors and IHC, the latter representing either the need to perform some diagnostic and therapeutic procedures to better stabilize the Patient eventually expected to get back home or, in the worst case, the occurrence of temporary or permanent disruption of the family support possibilities.

Ambulatory Palliative care (APC) is an important source of proper Hospice admission requests, as well as an effective and powerful interface especially for those Patients mainly suffering from pain but still able – if helped – to live their everyday life. Further relief can also be achieved for anxiety, fatigue and dyspnea (13). Some of them may need a Day Hospice regimen to carry out procedures such as central venous or peridural catheterization, if useful for symptoms’ control. So, if in a network perspective Hospices have more input than output options, APCs have less input sources but a big potential to provide useful suggestions about the care setting to activate especially early in the disease process (14).

The fact that each single setting has at least one output source and at least a positive comparing match between the in and outputs, suggests that the network diagram looks more like a cloud-distributed rather than a monolithic system.

Lesson learnt and conclusions

The mere setup of a Palliative Care service with its several components, if not correctly “advertised”, may produce confusion and misuse. During the summer 2011 we organized training courses for Family and Hospital doctors belonging to 5 Health Districts serving an area of about 500.000 inhabitants, in order to help them to better understand the scope and possibilities offered by our Palliative Care centre. An easy to fill-in admission form was issued and made available on-line to doctors, so that the adequacy and numerosity of admissions increased, meeting the favour of the public.

Palliative Care services are a real opportunity for Patients and their families as long as they are easy and fast to access. Thus, it is necessary to improve the medical and public awareness about the subject, also fostering and promoting association of citizens to keep up their guard and be extremely vigilant about the right to be provided with adequate care wherever they are rather than “centred” in units. We founded the not-for-profit organization “Gli Amici dell’Hospice Don Uva di Bisceglie – Onlus” (“friends of Hospice Don Uva in Bisceglie”) during the summer 2011 ( www.amicihospicebisceglie.it ).

For the Patients and their families, bureaucratic barriers are a tremendous source of stress and demoralization, so Health Districts should simplify as much as they can all the admission procedures and administrative requirements, both on the public and on the medical side. Psychologists and Social workers play a key role in this field as long as they act as an effective interface between the System and the Person.

Also clinical records should always be updated and readily available, and a degree of inconsistency, if any, represents a reason for stress and medical errors, especially when changes in the care setting occur during the palliative trajectory.

References

1. “Disposizioni per garantire l’accesso alle cure palliative e alla terapia del dolore” (Right to access palliative care and pain medicine). Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana, Serie Generale n.65 del 19 Marzo 2010. Available online at: http://www.normativasanitaria.it/jsp/dettaglio.jsp?attoCompleto=si&id=32922 last accessed Jan 8, 2012

[1] 2. Thorpe G. Enabling more dying people to remain at home. BMJ. October 1993;307:915-918

3. Editor’s note. Access to Palliative care varies widely across Canada. CMAJ. February 8, 2011;183(2)

4. Editor’s note. England examines funding options for end-of-life care. CMAJ. May 17, 2011;183(8)

5. Van den Block L. et al. Care for Patients in the Last Months of Life. Arch Intern Med. September 8, 2008;168(16)

6. Beccaro M. et al. Inequity in the provision of and access to palliative care for cancer patients. Results from the Italian survey of the dying of cancer (ISDOC). BMC Public Health. April 27, 2007; 7(66)

7. Lynch T. et al. Barriers to the development of palliative care in Western Europe. Palliat Med. December 2010;24(8):812-819

8. Lynch T. et al. Barriers to the development of palliative care in countries of Central and Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States. J Pain Symptom Manage. March 2009;37(3):305-315

9. Relazione sull’attuazione delle disposizioni per garantire l’accesso alle cure palliative e alla terapia del dolore. Camera dei Deputati della Repubblica Italiana. Doc. CCXXXVIII n. 1, 2011

10. Corli O, Pizzuto M. Guida ragionata all’impiego dei farmaci oppioidi nel dolore da cancro. Roma: CIC Edizioni Internazionali; 2009

11. Brink P., Partanen L. Emergency Department use among end-of-life care clients. J Palliat Care. 2011; 27(3): 224-8

12. Barbera L. Why do patients with cancer visit the emergency department near the end of life?. CMAJ. Apr 2010; 182(6):563-8

13. Paiva CE. et al. Effectiveness of a palliative outpatient programme in improving cancer-related symptoms among ambulatory Brazilian patients. Eur J Cancer Care. Jan 2012; 21(1):124-30

14. Griffith J. et al. Providing palliative care in the ambulatory care setting. Clin J Oncol N. Apr 2010; 14(2):171-175

Test di autovalutazione: per il test collegati alla pagina http://74.82.39.9/painforum/wordpress/?p=112 – la password di accesso è pnmpnm